|

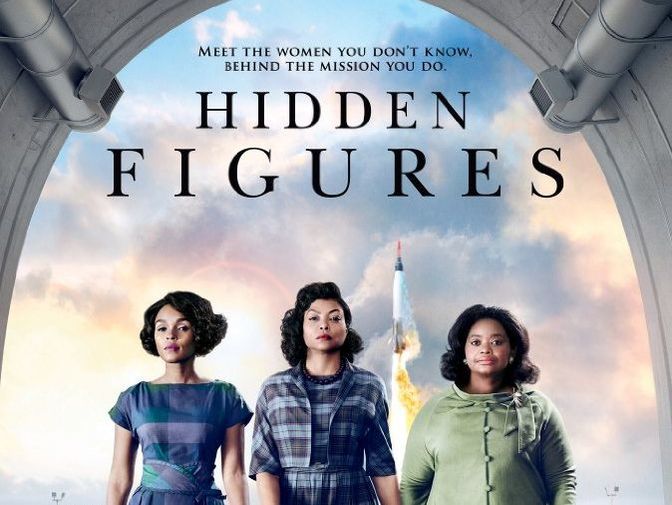

After winning the SAG award for Best Ensemble Cast, topping the box office at a current count of over $100 million, and earning an Oscar nomination for best Picture, Hidden Figures is easily one of the bestselling and most critically received films of the year. Based on the book written by Margot Lee Shirely and adapted to the screen by Allison Schroeder and Theodore Melfi, Hidden Figures illuminates the work of African-American women who helped launch the American space age into being. Our first introduction to Katherine Goebbels (later Katherine Johnson) is as a young girl. Recognizing her intellect, Katherine’s teachers tell her parents that she is ready to jump ahead to the high school level. The catch is that the only school she can attend for African Americans is a far distance away, but her teachers are so invested in her progress they have put together a fund to help Katherine get to school. This moment only last a few minutes on the screen but it sets the theme for the rest of the film; it represents the success of the individual as a byproduct of the support and unity of the community. Fast forward years later, Katherine is an adult and already working for NASA alongside Dorothy Vaughn and Mary Jackson, two remarkable women in their own right. After some car trouble, all three arrive at headquarters where they work as computers crunching the numbers for the space program. Katherine is assigned to the team preparing the math for astronaut John Glenn’s first orbital launch. Any other biopic would limit its focus on just Katherine’s struggle, and there are many: from being suspected of being a spy to fighting her way into the meetings about her own launch numbers, but Hidden Figures takes the extra effort to follow Dorothy’s struggle to gain the position of Supervisor that she deserves and Mary’s path to become the first African American and woman engineer. In a standard biopic, each woman could arguably have their own film at the exclusion of the others, but instead Hidden Figures presents their stories together because they all face the same overt racism from different fronts. The film resists showing the space age as just the act of a few exceptional women. When IBM’s technologies threaten to make the computers obsolete, rather than just save her own job, Dorothy teaches herself how to program the machines and then trains all the other computers in the colored women’s division the same skill. Just as Katherine’s teachers and her parents pulled together to ensure that she had access to the best education possible, the computers pull together to make sure that each member succeeds even if some like Mary, Katherine, and Dorothy happen to excel farther. Success is not something achieved alone but through the progress and support of the collective. Hidden Figures is worth watching because it gives a different perspective on the space race through the lens of race, gender, and challenges the biopic genre by presenting the group versus the individual. The performance of the three key actresses grounds the film and provides its strength. From Taraji P.Henson’s pure power during her climactic speech, Janelle Monáe’s gravitas in the courtroom, to Octavia Butler’s control and subtly in the bathroom scene, each actress proves she is more than deserving of her critical acclaim. If you can see this film in theaters, do so today. By Jessica Flores  Directed by Caroline Bottaro, begins with the morning routine of a sensible maid, living on the island of Corsica. Her cleaning of hotel rooms and her husband's painting of ships supports their daughter and they even can save for their teenage child's summer literature trip. The island life is beautiful and the family has all that it needs. But eventually Helene, the cleaning lady, la femme de menage, a title she always winces at, wants more. But it's not money and it's not a new home. Her curiosity is awakened by an English speaking couple who play chess. Helene cleans their room while the couple plays on the balcony and she can't help but notice the connection this game gives the pair. The woman wears a beautiful lacy golden slip, that she leaves behind and Helene keeps it for herself. For her husband's upcoming birthday Helene buys a chess-set. The commentary from friends at the table while they drink wine is that while none of them knows how to play, it is known chess is good for the intellect and so, why not? Ange, her husband, takes no interest in the electronic chess set whatsoever and is worried that it cost a lot. Helene wears the sexy slip but her husband takes little notice and their marriage might seem to have a problem. She gets out of bed, goes to the kitchen and in the dim light takes out the chess game and begins to play. She fails and tries over and over again. Her interest leads her to take notice of Doctor Kroger's set. The Doctor lives alone and is a man subject to much viscious town gossip as to how his wife really died and why he lives alone so much. Little is known of him, other than he seems quite intelligent, has a wide array of books and thankfully for Helene, a lovely, large chess set. Helene cleans his house and asks him if he does mind spending the time to teach her how to play chess. She has an electronic set but it's really not the same. He wants to know why him? She reminds him that chances are, she's not going to find anyone else to teach her to play. He can't argue with this and so they begin. Helene becomes quite good and the townspeople think it's crazy a woman and a maid, no less, has become so attached to the game. She wins her first tournament. And as she has her photo taken for the paper she sees the woman on the balcony who asked her a long time ago if she liked to play. The woman smiles then disappears. Helene boards a boat for the mainland and then on to Paris for her next tournament. Her sweet husband paces below on the walk. She is ready for the challenge. By Sarah Bahl Julie Taymor’s Oscar nominated film Frida (2002) chronicles the life of the famous and infamous, Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. The film opens with Frida, played by Selma Hayek, as she is being moved out of her house while still in her bed. As the movers carry her through the home, each room seems to leap out of Frida’s paintings to the screen. Full of color and odd assortments, peacocks in the garden, masks, self-portraits, these early shots show Frida as both the subject and creation of her art. Taymor’s direction blends subject with form throughout the biopic, reenacting many of the key events in Kahlo’s life with the imagery popularized in her work. The trolley accident that changed Frida’s life takes on an artistic lens bordering on the surreal. Just before the accident occurs, another passenger pours glitter-like gold flecks into teenage Frida’s hand. When the collision happens moments later, the gold flecks fly into the air and fall over Frida’s bloodied body creating an image that is a mixture of beauty and horror. The dream sequence that follows breaks into a new visual language. A montage of puppet skeletons abstractly depict Frida’s recovery in the hospital, some wearing nurse uniforms and a dislocated voice, most likely a doctor, diagnosis Frida’s condition. The skeletons move around against a black background, shaking and dancing in an impressionistic nightmare of the three weeks Frida spends in the hospital. Throughout Taymor experiments with different styles to represents Frida’s imagination, torment, and talent. As Frida recovers, her pain is directly funneled into her art, first when she paints a butterfly on her body when her teenage boyfriend tells her he is leaving her for Europe, then continuously throughout the film through the highs and lows of her life. But the film also makes the distinction that Frida is more than just a painter by also focusing on her sexuality, activism, gender non-conformism, and turbulent marriage to Diego Rivera. Unapologetic about her choices in clothing, partners, or politics, the film presents its subject without fear of tarnishing an image, something that is rare for biopics. The film draws to a close by contextualizing the opening scene as Frida arrives to her first and only solo gallery in her home country. Subverting her doctor’s orders in true Frida fashion, she has turned her mandatory bedrest into a dramatic entrance to the event she has waited for her entire life. As with her art, the imagery of Frida entangles defiance, agony, and joy with the very last scene implying Frida’s death. Choosing to close on a representation rather than a reenactment, Frida holds its own as not just a retelling but as a living-painting. Melding the representation of Hayek as Frida in a moving painting, Frida smiles while sleeping in a burning bed underneath the literal specter of death. The image does not replace the artist’s original work, but instead adds movement on the screen to bring her work into another phase of life. Jessica Flores  The Nape of the Neck by G. Gluckmann The Nape of the Neck by G. Gluckmann Now that we know who has won, it may be time to turn to the matter of a Victorian novel about a governess and how she finds her way. And in the case of Lady Audley, her path is a little windier than most. The sensationalist novel begins with a variety of characterizations. Firstly there is Lucy Graham, the uniquely fair and pretty governess who works under the care of a Sir Michael Audley, who falls in love with the woman and wishes to marry her if she may tolerate him well enough. And so they are joined as man and wife and Sir Audley becomes, for a time, one of the happier men to lord over the estate. In Lucy, he regains his youth, and finds in her a care that he never had for his deceased wife, who he married in order to gain land that he never really needed in the first place. Then like a movie played out wherein the characters are not introduced in a direct right, we get to know, a George Talboys who is returning to England from Australia after having been away for a couple of years. He has made his fortune and is in search of his wife who he left for a time. Upon return to his homeland he finds her to have died and left in his care, a son, who has been kept with his grandfather. George has no interest in raising his son, and stays with his friend Robert Audley, nephew to Sir Michael. But George's thoughts toward his deceased wife do not end, and on his way to visit a neighboring town, he disappears, leaving Robert obsessed in solving the answer to the life of his missing friend. And in Robert's quest, the secrets of Lady Audley are revealed. By Sarah Bahl Pariah is a coming of age story about 17-year-old Alike, who struggles to express her sexual identity as she tries to balance her home, school, and love life. The film is a poignant portrait under Dee Rees’s direction and writing, seamlessly showing Alike’s yearning, heartbreak, and resurgence.

|

Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed