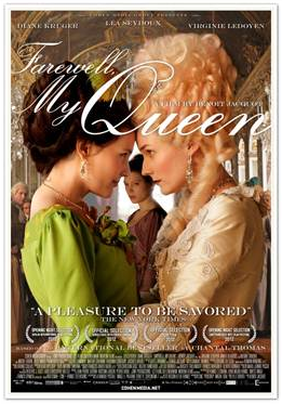

Coco Before Chanel, is a film about the rise of a woman, born into poverty and determined not be another drudge in the system. (Our lead character is a born snob.) The film begins with two girls being driven in a simple peasant cart. It is 1893. They are taken to a nunnery, where the nuns wear incredibly starched wide sweeping black and white head covers, that are essentially enormous fabric triangles on their heads. Even for the nuns, 1893 was not an era of practicality when it came to fashion. Gabrielle Chanel and her sister Julie, are the two young girls in the cart. They are wordlessly and unceremoniously dropped off by their father for care within the abbey, that served as an orphanage for poor undesired girls and as a boarding house for wealthy young girls. Chanel waited for her father to come back every week while at the abbey. He never did. Chanel and her sister both become pretty women, working as seamstresses during the day and in a pub as singers in the evening. Their dresses are very simple. There is a huge difference in the style and the fabric of how the wealthy women dressed versus the working class women. For example, today, there is not a huge difference in the style, cut, color and detail of a suit Hillary Clinton would wear to work, versus, a secretary working as an administrator in any given office. In the early 1900s, differences in terms of style of clothing when it came to class were of incredible variance. Wealthy women had a marked amount of detail in their fabric, how their hair was done, and the jewels they wore. So much adornment. The working class women wore very simple, clothes of plain coloring, that differed greatly from the garb of the wealthy. At the pub, Chanel meets her lover and protector Étienne Balsan, who she insists on staying with, as she sees him as pivotal to her gateway toward a better life. It is Balsan, who christens Chanel with the name Coco, after a song she sings. The name does seem to suit her tomboyish nature and simple features. Coco, charms Balsan with her quaint mannerisms, her love for clothes, horses, and need to be something different. She is known to dress as a boy, most of the time. To forego the use of a corset and practice other such anomalies for the day. Coco, consistently wants to have more and be more. She realizes she will never have a stage career but the hats she makes are well liked and in demand. She has a knack for sewing. She leaves Balsan, who remains a supportive father figure throughout her life, for Arthur, “Boy” Capel, a friend of Balsan’s. Boy asks Balsan to have Coco for the weekend, which is how their love affair began. It might seem terrible today for two men to share a woman without complaint, but during the early 1900s in Europe it, was considered unseemly for men to rival each other for a woman. And if one man wanted to sleep with another man’s lover or even a wife, the husband in question should consider the offer a compliment, that another man would want his wife/lover. It was the culture at the time. Coco leaves Balsan, because he wants her to be his alone, and to have no other features. He wants her to become his wife and she says no. She wants a different future for herself. Boy is the man who supports her career ambitions. He lends her money to start her own business. With the money to launch her own creations on a consistent basis Coco Chanel leads the world of fashion in two manners. First, she lessens the differences in clothing when it comes to class. Her outfits are simple and chic. Second, she lessens the difference in clothing when it comes to gender. Her boyish, elegant simplicity is trademark of all her fashions. Her ideals matched wide sweeping sentiments toward womens' rights at the time. Chanel lead the world of fashion into incredible changes, that are very visible today. By Sarah Bahl  Farewell, My Queen (Les adieux a la reine) directed by Benoît Jacquot; provides a uniquely intimate portrait regarding the ending climax of King Louis XVI's reign. The intimacy is due to the perceptions of the story being told from the perspective, not of the reigning nobility, but from that of a top end servant girl, who works and lives among the most powerful members of court-life at Versailles Palace (about 14 miles from Paris). The film begins with a very realistic opening scene of Sidonie Laborde, on July 14th 1789. Sidonie, is the servant who drowsily and slowly wakes within a sun filled simple room, wearing loose fitted white night clothes and scratching mosquito bites as flies buzz around her. It is easy to feel the heat of the day in the room and one wonders how the nobility manage wearing so many layers of clothes during the summer. I find Sidonie's daytime work outfit to be beautiful and intricate. Her hair is simply placed on top of her head uncovered and she wears no makeup. Despite Sidonie's natural beauty, I realize what she wears is nothing compared to the detail and marked sophistication of Queen Marie Antoinette's unusually stunning garb. The Queen's eyebrows are light and when at court she wears full make-up. Within her private chambers, she does not. There are details within the film, that reveal the lack of hygiene behind the daily lives of those in court, despite all the finery. For instance; Sidonie's arms are covered in welts from bites and she wears the same dress everyday, except for one. How much the smell could have matched with the look is of question.It appears Sidonie only has three outfits. One, her nightdress which might be the same as what she wears under her day dress. Then there is a formal dress of her own she wears toward the end of the film. Though, the hygiene efforts do speak of the general standards throughout Europe at the time, it still causes one to wonder: if this is the standard for the fairly well off Sidonie, how much are the multitude of persons within France suffering on a daily basis? The servants seem to have enough to eat but no table manners. Sidonie, despite her well read proficiency toward life, has no idea how to eat from a fork, nor what to do with her elbows. It is a reminder of how, despite her education and natural intelligence, she is a servant. Kept to a certain place. Sidonie is awoken by a chiming clock, a rare treat for a servant girl to have in her possession. Sidonie is given the task of reading to the Queen. The Queen's attentions flit from one task to another. From plays to fashion designs, to rosewater ointment for Sidonie's welts. The Queen is married to the King, but they are never seen directly together until the King leaves Versailles. Why he is separated from his wife and children during such dangerous times for the family is not explained. It is not made known the Queen has children until toward the end of the film. It is a film very much about adult needs, desires, and games. The Queen makes her appetites readily known and she is familiar with both genders on the subject. Her true love appears to be for a high ranking noble woman and this love is known both to the King and the whole court. Marie Antoinette and the King see each other for one very dry, awkward parting farewell kiss with the children present. Sidonie holds true love for the Queen in her heart, until she realizes, she is just a pawn, in a brutal game of survival among falling powers. The Queen gets what she wants for the most part, and she plays very aptly with Sidonie's lonely emotions, in order to cull her into submission. Sidonie is also outnumbered both by individual powers and circumstance. There is really no outlet for an independent voice of her own within the confines of court life on the eve of the French Revolution. The most human factor in the film, is another one of the Queen's personal attendants, who implores Sidonie not to do what the Queen is about to ask her. By Sarah Bahl

Seraphine, Feuilles D'automne 1928-30 Seraphine, Feuilles D'automne 1928-30 Séraphine (directed by Martin Provost), recently screened at the French Embassy is a movie about the triumph of human character over circumstance. The story begins with a woman hunched over, collecting mud and water from a pond. She wears a blue shawl. Her body is dowdy, and her dress shapeless. She hums to herself and looks about her with adorable, inquisitive blue-grey eyes. She likes to sit in a tree and smell the air with the breeze blowing her forever unkept hair about. This is Séraphine, a servant for patrons in a fairly small town at the dawn of World War I in France. She manages, despite the plethora of errands she runs during the day, to paint. And paint she does. By creating mixtures out of nature and some bought supplies. Some stolen, as well. However she needs to paint, she does. She sings to herself as she paints, much to the non-entertainment of the dwellers one floor below her. She is lovable, weird, as awkward as she is natural, and very, very much herself. One of the tenants, Wilhelm Uhde, is renting a flat from Séraphine’s mistress. Uhde is a frontrunner in the art world and a well noted critic. He takes a liking to Séraphine and she to him. She lets him know she paints and the word of Séraphine’s exploits travels to her mistress; who of course, demands to see Séraphine’s work, only so she can mock it and tell Séraphine to give up. The mistress’s son, stands up for Séraphine’s work, and keeps his mother from throwing it away altogether. The piece is laying to the side on the wall in the dining room, when it is noticed by Uhde during a dinner. He demands to know who the painter is and the mistress reluctantly has to admit that it is Séraphine. Uhde becomes Séraphine’s patron and protector. He has to encourage her to sell her work and she seems reluctant because she is afraid of losing her place. Of breaking with the traditions within her own life of servitude. But Uhde convinces her and she agrees to exhibit and sell her work. It is a “pure” relationship as Uhde informs Séraphine that he will never marry a woman in his life. Uhde has to leave France as the War progresses but comes across her work at a local show many years after the War has ended. The two strike up a relationship once more and Séraphine’s art sells as part of what is known as the naïve genre. She continues to paint, but her relationship with Uhde is strained due to her spending habits. She spends more than is coming in and on the oddest things. Such as a wedding dress, when there is no actual wedding. Séraphine’s eccentricities descend into a sad outright madness. She dons her wedding dress and by herself in bare feet, walks through the town knocking on doors and leaving empty silvered candleholders on the doorsteps. At the top of the town stairs are local authorities, waiting to take Séraphine away, in a van. She seems to know why they are there and submits without any confrontation. She just gets into the van, barefoot and in her beautiful dress. The cinematography throughout the film is breathtakingly clear, as if to reflect the purity of Séraphine’s soul and intentions. Uhde attempts to visit Séraphine, but she is too far gone. He makes her more comfortable, by buying her a place in a home where she can be alone. And the final scene is of Séraphine, sitting down on a chair in the middle of a field by herself under a large, comforting tree. Séraphine had the courage to tell a story of a world that begins and ends within herself. She became known as Séraphine of Senlis. It is still not known exactly how her paintings were made. They are of fruits and trees, as if in a child’s dream. By Sarah Bahl The image is from madamepickwickartblog.com  A rendition of Giselle (1841) A rendition of Giselle (1841) To escape to the Kennedy Center in morbidly hot weather is a gift of itself. The plush red carpet is comforting and the hum of persons being shuttled in an orderly fashion to their seats is part of the veneer. Giselle being performed by the Paris Opera Ballet at the Kennedy Center is a gem to see. According to, La Maison Française’s information letter, the Paris Opera Ballet has not been to the Nation’s Capitol in 19 years. The ballet runs through the 8th. The First Act of the story begins with bright and natural woodland scenery. The floor is kept a simple wood and the costumes are elegant and rustic to reveal the simple peasant Giselle (danced by Isabelle Ciaravola). Her dress adds to the quaint rhythms of the peasants' motions as they celebrate the harvest. There are two men in Giselle’s life. One who she accepts and the other, she keeps at a distance. Her preferred man is Prince Albrecht of Silesia, who, tired of court life decides to dress as a peasant and woo the lovely and innocent Giselle. Her jealous suitor, the Gamekeeper Hilarion, unmasks Prince Albrecht, and in doing so reveals Albrecht to be already engaged to the noblewoman Bathilde, (dressed in highly refined and lushly embroidered costume to starkly contrast with Giselle being herself.) The sensitive Giselle dances to reveal her confusion and pain. She dies from the pain of her lost love and the competing men nearly duel over her.  Carlotta Grisi as Giselle (1841) Original Source Unknown Carlotta Grisi as Giselle (1841) Original Source Unknown The Second Act, is absolutely beautiful in an otherworldly manner, with a darkened woodland scene, as Giselle, now deceased has joined The Wilis, the spirits of young women, with the misfortune of death brought upon them before being wed. The dancers, in white spirit garb, are all the same height, and dance in unison to celebrate their current fate within the black woodland night. The Wilis enact revenge for their broken hearts by wooing young men into their world, never to return. Their first victim is Hilarion. Then, it would be Albrecht, as well, except Giselle convinces the other spirits to let him go, because she still likes him so much. And so the story ends. Giselle returns to her world and Albrecht remains within his own, much as it all began. The original costumes represented are by Paul Lormier, for the ballet’s initial 1841 production. At the time, Romanticism was in high fashion among the general populace in France and the costumes and ideals behind the ballet marketed to this particular niche. Lormier did much historical study to create as realistic a garb as possible. The current costumes represent the spirit of his work. By Sarah C. Bahl By Xin Wen When Louis XV was still alive, and when Marie Antoinette as a young dauphine was still popular among French people, she once wore men’s breeches and a riding coat. The audacious outfit gave her the fame of ‘the only man of Bourbon’. In fact, only after the revolution broke out, did she act as a political figure. At first she refused to leave France and then she wrote letters to her relatives in Austria with the hope that they would rescue her and her family. However, this time she was out of luck. After a very short stay in the Tuileries, in August 1792 she and her family were transported to the Temple, where they were captivated as prisoners. The royal family’s life in the Temple was filled with indignities: one of the queen’s valet recalled that the guards of the Temple even put their hats on in order to express their disrespect when they saw the royal couple. As for clothing —Marie Antoinette’s wardrobe shrank greatly: with the small amount of money the Commune de Paris gave, she ordered ‘two white bonnets, nine gauze and organdy fichus of varying sizes, one skirt, one white linen capelet, one black taffeta capelet, and three lengths of white ribbon, several shifts made from linen and muslin…’ (Caroline Weber, 2006, Queen of Fashion, page 255) Let us not forget this was a woman who used to purchase more than 300 new outfits a year, a woman who spent thousands of livres to comb her hair into a series of new styles, and a woman who was imitated by all the aristocratic women in France. However, when ‘the only living creature in France who still cried “Long live the King!” was a parakeet’ (Caroline Weber, 2006, Queen of Fashion, page 259), the crowd with admiring glances disappeared--partly because they were blocked by the tall, thick walls of the Temple, partly because they didn’t care anymore. After her husband was executed, Marie Antoinette wore a black mourning gown day after day for two months. Her body condition got worse because of the abominable environment of her cell; her hair became white as her trials went on. She was steady and calm in front of most of her charges; however, she couldn’t remain silent when she was accused of ‘incest’—having a sexual relationship with her son—then a 7-year-old boy. Though hard to believe, the aggressive revolutionists indeed invented this absurd accusation. Maybe they thought for a chief culprit who relentlessly depleted the French national treasury (though actually France’s aid for America also contributed to the depletion of the French national treasury), the charge of incest was something she deserved. On the morning of October 16, 1793, Marie Antoinette changed into her last outfit—a white chemise with the stare of a gendarme. This scene reminded me of the stripping ceremony she went through 23 years ago. Over these years she failed as a queen, but succeeded as a fashion example. In Caroline Weber’s account: ‘She slipped into her plum-black shoes, a fresh white underskirt, and her pristine white chemise. To complete the ensemble, she put on the white dishabille dress Madame Elisabeth had sent her from the Temple and wrapped the prettiest of her muslin fichus around her neck. Marie Antoinette’s final fashion statement eloquently condensed her complex sartorial history into a single color with a host of different associations: white.’ Marie on her way to her execution, by Jacques Louis David

According to Stefan Zweig, only one person was truly woeful after Marie Antoinette’s death: her lover from Sweden—Mr. Ferson. He could never forget the glamour and radiance of the Austrian lady. However the turbulent wave of history did not have the leisure to mourn an evil queen’s death, or an old man’s misery. It took 22 years until people identified the corpse of Marie Antoinette among hundreds of dead bodies. Sarcastically, it was a piece of cloth that led the searchers to Marie Antoinette, in Zweig’s words: ‘A moldering garter enabled them to recognize that the handful of pale dust which was disinterred from the damp soil was the last trace of that long-dead woman who in her day had been the goddess of grace and of taste, and subsequently the queen of many sorrows.’ References : Stefan Zweig, <Marie Antoinette>, Pushkin Press, 2010 Caroline Weber, <Queen of Fashion>, Henry Holt and Company, 2006 The sketch came from Wikipedia. |

Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed