|

.Summer camp can be one of fondest memories from childhood, where we make lifelong friends, learn new skills, and have experiences that help define ourselves. Girls Rock DC combines all of these through its summer music program. For the past 10 years, Girls Rock DC has been on a mission to empower young girls, gender-non conforming and trans youth aged 8 to 18 through music instruction. In a week long program, camp participants are taught how to play instruments, attend workshops, form a band, and perform an original song or musical impression at the 9:30 club to exhibit their new skills. The 2017 Showcase next will occur tomorrow, Saturday July 1st.

A Woman’s Bridge was fortunate enough to speak with Katie Beckman-Gotrich, communications committee member and volunteer, and Annie Lipsitz, one of the founding members of the organization, during this year’s camp session. This week, Girls Rock DC is celebrating its 10th anniversary. Can you go into detail about how the DC branch of Girls Rock was founded? How has the program grown over the years? K: There are four founding members that are still a part of the leadership team Jen Fox-Thomas, Tiik Pollet, Shelly Rush, and Annie Lipsitz. Almost all of the founders come from an community organizing or education background. The whole founding of Girls Rock DC is from a feminist slant,[and] in this moment we are very much focused on inclusion. All movements are tied together. I’m very excited to see people who look like our campers showing up to volunteer today. It’s a very diverse group. We’ve always had diversity of various sorts but this year you can feel the difference. We meet as a team for a morning meetings, then an afternoon meeting when all the kids are in assembly, and then after the kids go home in the evenings. We have some great conversations about how we conduct our camp and having those diverse voices are so vital. A: Our first camp was the summer of 2008. The organization was founded in October 2007. I’ve been on the leadership team for 9 ½ years. I also do a lot of our fundraising for grants, financial donors, and benefit events. At camp, I’m a band coach though I don’t have much musical experience. We’ve made space for folks who don’t have musical experience to play that role and be involved. Your mission statement says that the camp provides a supportive space for all girls regardless of socio-economic class, race, gender identity, or sexual orientation, to become self-empowered while learning about music. Can you give examples of how girls are taught these skills and given an inclusive space? K: On the first day of camp, during their first assembly, there’s a list of non-negotiables. These are our values and the youth add on to the lists. [It’s] a guideline of how they’ll treat each other and what’s important to them to feel represented. To me, I feel honored that they share that their name has changed, that their pronoun has changed. I guess to me honored is the best way to phrase it. The other things that we do at camp is show that there is support. If somebody needs a quiet space or a personal space there is a place for that. There’s also a volunteer counselor who is trained and a nurse. So we can be amenable to all sorts of needs and there’s the proper support to have space and feel things without feeling ostracized. A: Over the last couple of years we have started asking volunteers and campers which pronouns they like to use and also if they have a preferred name that maybe isn’t their legal name or the name they go by at school. We’ve always asked that but this is the first time we’ve put their pronouns and preferred names on their name tags. We’ve done a lot, starting on day one, introducing what a gender pronoun is, why it’s important to ask people what their pronouns are, and not to make assumptions about that, and to ask people what they want to be called. That, I think, has taken root with a lot of the campers. It’s also been really important with a lot of our campers, some of whom are returning using different names or pronouns than they used last year. It’s really important introducing kids to more than two options as to what a gender identity can be or what a pronoun can be. Even though we introduce it on the first day of camp, we constantly reinforce it at the beginning of workshops and with name tags. We’re in a school that is lending us space, so the multi-stall bathrooms are labeled boys and girls. Maybe you saw the Gender Liberated bathroom [signs]. Then there are single stall bathrooms for folks who don’t want to use a Gender Liberated bathroom, but we didn’t want to have that separation between only boys and girls which is really uncomfortable because a lot of our kids and volunteers don’t necessarily fit into that binary. Those are a couple things that we’ve done. What are do you hope your campers will learn from this experience? What values do you hope campers will walk away with after camp ends? K: Our hopes for our campers are that they feel comfortable being themselves. I’m an educator [and] I taught ESOL for adults. The biggest barrier when trying to help someone learn is fear. Once you create a safe space where they [are not] afraid, [even though] there can be a lot of stuff that’s happening in their life, when they enter that community space, if they feel safe, anything can happen. I’d say our hope is that they still feel that community support after camp. Once they’ve tapped into who they really are, they don’t want to stop and they’re going to tell people about it. They want to keep being who they are, they want to be inclusive [community with] other people. And that’s incredible, because then their talents are going to shine. They excel. So our hope is that we’re changing the world through these youths. A: We have year-round programming. Summer camp is our biggest program and definitely how the organization was founded, but we have an afterschool program, GR!ASP, that was running at two schools in DC last year. We have our adult camp which won’t be until 2018 next year, called We Rock! Camp. After this [summer] camp we have a lot of organizational work to do, right now we’re primarily run by volunteers. I think we still have some visioning and mission building to continue this social justice thread, to continue with this equity, inclusion, and value based work we’ve engaged in over the last couple of years. We take a little bit of a break in the fall but it’s time to regroup and reground ourselves in our mission, our values, and our principles to see how we can continuously connect with our campers from the summer and how to build our organizational structure in a more sustainable addition. How do you think camps like this one will impact the music industry? K: I think a large part of it is taking up space so that they will feel comfortable about making choices and not being differential. I think they’re going to make their own choices about what they consume, whether it’s musical media or media-media. By being themselves, they’re going to take more ownership of their choices, whether it’s relationships, consumerism or learning. One of our volunteers is going to WAMU and is a former camper. That’s part of the beauty of this is that we bring people who are different together to be inclusive and then they take that back out into the world. All these kids do amazing things with their instruments in this very short time and then they don’t have to be afraid of other things. Hopefully this diminishes their fears of trying other things like math, science or art. You can do a lot from where you are by being who you are more honestly and openly. Tell me about the showcase. What have the campers been working on? K: So the campers have been working on their songs, or musical expressions. They get 5 minutes and can do pretty much whatever they want. Our job is to just facilitate the creativity. Sometimes they perform more than one song. They’ve been working on their instrument and getting tight with their band or DJ crew. What changes have you seen over the years? A: Even just in the past year or two has put in some very concrete things, like messages about equality and equity. We changed our mission statement to include not only girls, but also gender-non-conforming, gender non-binary, and trans-youth, and we added some additional language [about] accepting people from all diverse backgrounds, racial, ethnic, social economic, all-across the board. Last year we committed to offering stipends to all of our volunteers, which we’ve never done before. We saw that as a really big step to making our camp more accessible to a wide and diverse range of folks who can offer their skills, talent, time, energy, expertise, and spirit to the camp, our programing and especially also to our youth. It’s been a really huge goal of ours to continuously offer and provide our kids with youthful and relevant role models. Since day one we’ve been saying that, and I think in the past year, year and a half, we’ve done a lot of really concrete things to make that more possible for them to see themselves reflected in the people here at camp. Tickets for the 2017 Camper Showcase can be purchased here. The camper showcase is on Saturday, July 1st at the9:30 Club. Doors open at 10:30am. To volunteer or donate to Girls Rock DC or any of the other programs, please visit the organization’s homepage. By Jessica Flores

1 Comment

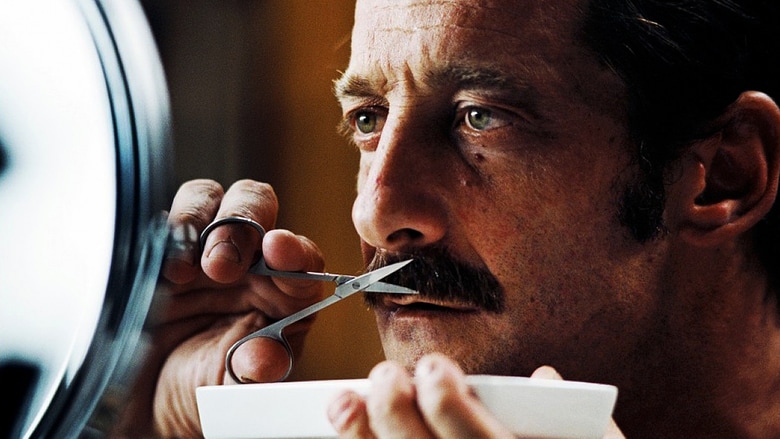

Is about the stresses of modern life and how they lead to self destructive tendencies. Hannah is in high school, and as a good student and talented dancer she hopes to get into New York University. The Ann Arbor teenager is working on a college essay when she is introduced to a Pro Ana site by her friend, Kayden who also dances and is quite tall and thin. Pro Ana sites are dedicated to losing weight, for the most part. Hannah asks who the "Ana" is that people on the site keep writing to. Her friend explains it stands for anorexia. Hannah takes an interest and signs herself up one night, asking other chat members if she is the only one who can't stop eating peanut butter. HipPopK replies that late night cravings are the worst. HipPopK has "don't eat" carved into an effeminately displayed stomach. Hannah asks if that is a real photo, which brings to light the world of ghosts that is an online chat forum. HipPopK asks if she is impressed or grossed out. On the site Hannah gets lured under Butterflyana's wings. She pushes Hannah to lose 20 pounds in 20 days. Which is possible if one stops eating to an extreme. Hannah loses weight very quickly and her dance teacher, Miss Christie becomes concerned. Hannah is angry when Miss Christie tells Hannah perfection is not always a good thing and later inquires if Hannah is feeling alright. Hannah's mother gets her brother to break into her computer so they can track what sites she is on. The Thinspiration site is discovered and Hannah's mom becomes desperately worried. During this time Hannah's brother, Joey, continues to diet for wrestling. Their father constantly pushes him to stay very thin despite Hannah's dieting issues. Eventually the mother notices moths in her daughter's room and opens the closet to find decaying dinners as Hannah has been stashing her food for some time. Treatment can cost up to 90,000 dollars and Hannah's mother is willing to sell the house to make her daughter better. Hannah does become well again but only after Joey dies, as his heart gives out during a wrestling meet. He had been HipPopK. Hannah goes to meet the real Butterflyana and finds that she is an impoverished girl who needs help. Though, the acting is on par with a Lifetime film, it is worthwhile to see as it brings to light the role the internet plays in eating disorders. A relatively new network brings people together in ways they would never have met before. What might have been kept to a journal is written online. And for those suffering from eating disorders this is not necessarily a good thing. By Sarah Bahl Corinne Cannon started the DC Diaper Bank with her husband in 2010. The DC Diaper Bank strives to supply low-income families with much needed diapers and supplies. A Woman’s Bridge recently spoke with Corinne about the organization and its founding mission. How was the DC Diaper Bank founded? We started in 2010. In 2009 we had a son named Jack, who is a fantastic little guy today but was a very difficult baby. He was a baby we had planned for and we had the resources to have, but were overwhelmed with how difficult it was to be a parent. We had a night with him where I had an overwhelming urge to hit him and it really scared me. I have come to know that nearly every mother reaches that point, and it’s a natural part of parenting to reach that point of parenting, but it scared me. I wondered, what happens to the mother who doesn’t know that—the mother who did not plan to have a baby? What happens when you do not have someone to go tag-team out? What’s happening to that baby and what’s happening to that woman? I found out that a lot of them needed diapers. They needed diapers because they’re not covered by food stamps, they’re not covered by, Women Infant and Children Food and Nutrition Service (WIC) and they are just incredibly expensive and more expensive in poorer neighborhoods. So when I was calling organizations asking how could I help, what I heard over and over again was one of our highest needs were diapers. So I figured I’d work with the existing diaper bank, but then I found out there wasn’t one. We did a lot of research, a lot of business planning, and on my son’s first birthday we incorporate the first DC Diaper Bank. We wanted to create something that would be an ongoing resource for the region and would approach the issue as a regional issue. Not just in Virginia, D.C., or Maryland but the whole area. How many parents struggle to find clean diapers for their infants? About 1 in 3 women experience diaper needs (not having enough diapers for their child on a regular basis). The numbers may be a little higher because we have a lot of working families that are stretching diapers, and that’s keeping a diaper longer than they should. A lot of American families don’t have the resources and just [barely] meet basic needs for themselves and their children. So for our region, we’re talking roughly 35% of the children are in low income environments right now. There are certainly pockets that have more than that, different parts of the region have different levels of poverty, but we’re talking across the board. You need $100,000 to raise two children in this in this area and that’s to just to raise them, no extras. The cost of living is astronomically high and the disparity between those that have and those that have-not is really quite extreme here. What strains and difficulties does a shortage of diapers cause for parents? What are the deeper implications about the cost and lack of resources for purchasing diapers? At our base we are an anti-poverty organization. People say I’m interested in diapering the world, but I’m not interested in diapering the world. I’m interested in making sure families have what they need to thrive and that really comes down to the lived reality of poverty. One of the things I think we do really well is we open up people’s eyes to what is it to live without resources. When our volunteers come in, the questions they ask seem like really simple questions but our volunteers are asking them for the first time. What do parents do when they don’t have enough diapers? I think that really touches on the divide we see between those who are struggling and those who are not. Their lives are lived in very different spaces and in very different ways. A lot of what we do is try to raise awareness and from that awareness have people say “What would it be like if I did not know where my next meal is coming from? How would I get to work tomorrow because I didn’t have transportation funds?” and then ask “What should I be doing? What questions should I be asking of people who are elected, of my school system, of my employer? What should I be requiring and what should I be pushing for families that can’t have their voices heard?” Poverty is not separated out. They’re all the same issue. They’re all interconnected. We live in a land in which there is more than enough for everybody and the fact that we have children that are going hungry a mile from the white house is not only disgusting, it shouldn’t be. This work is about having that conversation expanded. I think diapers are a way of doing that because it is such a physical experience, not to say that hunger isn’t, but every parent has been in a situation when they ran out of diapers. They know what that feels like even if they don’t know what hunger feels like. This is a way to hook onto that experience and expand on it. How can the public become more involved in helping the DC Diaper Bank as well as being engaged with the community? What you need to do is be a voice. WMATA is thinking of cutting a bus line right now because “nobody” uses them. Who is that nobody that rides that bus line? [The school system] is talking about getting rid of school lunches because that’s not what the school system is for. Who will that impact? We need to talk about poverty. We need people to know that 50% of American babies are on some form of WIC. That’s a massive number of children that’s not being discussed. The thing this organization most needs are for people to have those conversations and for people not to be afraid of it. There’s a lot of fear in talking about poverty because you don’t want to talk about it incorrectly, you don’t want to say the wrong thing. You’re going to say the wrong thing and that’s ok. There is no right way to talk about children who are hungry, there is no PC way to talk about it, it’s a horrific thing. We should be discussing it more, we should be outraged by it more than we are, and we should be trying to find creative solutions. But the first step that most of us have not taken is discussing it and acknowledging it. You are called the DC Diaper Bank but you also have a program called The Monthly. Could you elaborate on this program? We do a little bit of everything. We do food and formula, we are actually a registered food pantry. We do adult food, baby food, hygiene items, shampoos, deodorant, and we just started a program called The Monthly which is collecting period products for low income clients. What our families really need are sanitary pads, more so than tampons. There are a variety of volunteer and donation opportunities with the DC Diaper Bank, from monetary donations, donating requested materials, become a diaper ambassador, and more. Stay updated with the DC Diaper Bank on Facebook and Twitter. By Jessica Flores Emmanuel Carrere's highly psychological drama is about details. Light reflects off darkened water. A man in a bathtub splashes away shaving cream as he shaves off his beard. He mentions shaving off his mustache. His wife, Agnes, comments that she has never seen him without it then while playfully sitting next to him on the side of the tub asks how he can stand the water being so hot.

She leaves to go down the stairs of a modern and cleanly furnished home. He asks her if she can turn the CD on to start and she agrees. Then Marc, while still in the tub begins to trim his mustache. He does so layer by layer. Then he places on the shaving cream and the mustache is eventually gone. Its remains are placed into the trash and then rinsed out of a tray. Their lives seem clean, neat and orderly. When Agnes gets out of the shower she asks Marc to hand her a towel. He wraps her in it while ducking his head behind hers as they rest in front of a mirror. He eventually pops his head out. She says she is not opposed to the idea but they are already running late for a dinner with friends. Marc is stunned. Agnes walks away while he stares at his fully shaven face in the mirror. During the car ride to their friends Marc says he will just find parking on his own and that Agnes can go on ahead inside the apartment. Agnes offers to stay with him, but he insists. She walks away and then stops and turns around back to the car. His eyes light up as if he's hoping and relieved that she will finally notice his lost mustache. She asks him to hand her the party gift that they have. He gives her the wrapped present and she continues on up. Once he gets inside, Marc is not warmly welcomed by Serge who is Agnes's old boyfriend. Serge and his wife Nadia have a daughter who will not say hello to Marc and it is a tense dinner. No one mentions Marc's shaven mustache though Marc is reminded by Serge to compliment Nadia's new haircut. Which he does. During the meal, Serge tells an interesting story about Agnes. That while they were on vacation during the winter with friends in a cabin they were told to keep the heat on low in every room so that way all the rooms could be heated without the fuse blowing. The first night there, the fuse blew and the heat was turned on all the way up in Agnes's room. She denied doing anything to the heat. The next night the fuse is fine and everyone thinks Agnes has learned her lesson only to find every other room is at - 5 degrees while Agnes's room has the heat on high. Someone had turned off the heat entirely to the other rooms. Serge says he admires Agnes for not giving in and admitting she did it. She says that's because she never did. On the car ride back Marc and Agnes begin to seriously quarrel. He takes her hand and places it on his face asking repeatedly how she could not notice. Agnes later insists he never had a mustache. They call their friends in the middle of the night as their fight continues and neither Serge nor Nadia can remember the mustache. Later Serge says that Marc has not had a mustache in 15 years. Marc begins to act aggressively and strangely even going so far as to dig the remains of the mustache out of the trash. Agnes calls for professional help to take Marc away but he overhears her talking about it with a friend and runs away to Hong Kong. His passport photo shows a man with a mustache. As did other photos of him on vacation in Bali. In Hong Kong he is allowed to see things with his own eyes rather than what Agnes tells him. But she finds him. By Sarah Bahl  A Woman’s Bridge spoke with Carol Loftur-Thun, Interim Executive Director of My Sister’s Place, the oldest women’s shelter in the DC area. My Sister’s Place offers a variety of services for women escaping domestic violence including emergency shelter, caseworkers, and programs for permanent housing. For help and information about leaving a domestic violence situation, click here. For the 24 hour emergency hotline run by My Sister’s Place, please call 202-529-5991. My Sister’s Place is DC’s oldest domestic violence shelter. What inspired the founding of MSP? Can you describe how the public’s reaction to domestic violence has changed over the years since My Sister’s Place was founded? My Sister’s Place started through the Women’s Legal Defense Fund and Junior League of Washington in 1976. We started as a hotline, actually, and we were shocked by the level of domestic violence that was happening. It was clear that help was needed. 1979 was when the shelter was started. Our founders’ philosophy was one of empowering women and that is still our philosophy today. We emphasized self-help, provided a place to stay and resources, and our staff members are also survivors of domestic violence. In those early years, the approach was very self-help oriented which was believed to empower women. It helped some, making them highly motivated by offering a helping hand and giving them resources. Others found themselves floundering a bit and that model didn’t help. We now know that trauma changes how your mind functions. The research wasn’t there then, but we now know how trauma makes memories fragmented, changes thinking, so making decisions to move forward is difficult. In the 90s, MSP did a research study talking to clients and staff. There was a need for a more professional all-purpose survival skills, not just an empathetic hand. We began a new chapter of a more professional approach that helped some clients. In terms of the public reaction, when the awareness campaigns started in the 70s, domestic violence was culturally still considered acceptable or private. It was seen as something for the courts to handle or a man and woman’s problem. As time has gone on, the public has realized the larger implications of domestic violence. Because the trauma has generational effects, children of abuse have a hard time in school and the abuse negatively promotes mental illness and drug abuse and even has direct health impacts. Domestic violence can cause an increase of heart disease and stroke, something like 70-80%. When people are threatened, our body has that fight or flight response and if we can’t actually take flight or fight, it causes a lot of internal damage. Chronic stress takes a toll on our physical and mental states. These effects are not just on the parents but on the children as well. Domestic violence also has this wide range of impact on our society. A 2010-2011 study said 1 in 4 women will experience domestic violence in our lifetime. The data for men is not as pronounced. The statistic depends on the study, but 1 in 7 or 8 men reports physical abuse. Women are more likely to experience severe physical injury including homicide. Both among men and women, we have epidemic levels of domestic violence. This is widespread, with severe negative impacts in America and worldwide. Loss of work productivity in the workplace runs to billions of dollars. Increased risks to law enforcement is another consequence. Domestic violence seems to be a major factor in recent terrorist incidents. Here in our area, the DC sniper attacks happened as a part of his plot to kill his wife. In the public, it has gone from a private matter to this is a very dysfunctional and unhealthy kind of relationship dynamic that causes victimization and tragedy. Could you elaborate on how MSP helps women transition to permanent housing and why this process is so important for breaking the cycle of domestic violence? Do other shelters focus on this process as much? The evidence shows safe housing determines if abuse victims can break the cycle. Survivors can include women, men, and LGBTQ individuals. We are increasingly talking about survivors as more than just women. There’s been a change in that language over the past 10 years. Safe and stable housing is one of the pre-conditions for being able to move forward. Without a safe place to live, survivors are more likely to go back to an abuser or start a new abusive relationship. Unfortunately, we hear so many stories where women stay because they don’t want to be in the streets with their kids. We do invest the time and attention in each family to make sure they go on to safe and stable housing. Our emergency shelter usually lasts 90 days, but we have let women stay up to a year. The old model used to be you had a set time, about 30 days to 90, to figure it out. Now, we are able to offer women more options. I wish we had more funding to accept more clients into our programs, because each day we see women beginning to lead independent and healthy lives for their children. In our programs, what makes a difference is highly skilled case management. It’s expensive but we believe it is worth it and makes a difference. At the end of the day it’s more cost effective; we’re not just cycling people through our shelters, they’re actually getting someplace where they can be safe and stable. In our RISE program, the vast majority of our clients have stayed in the apartments we have helped them lease. Some moved to other apartments but they are in stable long term housing. The challenge is affordable housing. It’s a problem for many in the area regardless of domestic violence. A significant number of managers do discriminate against domestic violence survivors. The application fee can be a lot and discourages many. Domestic violence victims have to put in a lot of money without possibly getting an apartment at the end. All shelters are focused on housing, but MSP is different in that we are low-barrier but we are more rigorous in our expectation. We offer voluntary services so clients don’t have to attend our services, but we do utilize a number of techniques to motivate them to use our resources that are provided along with shelter. We believe this does help them for ready and stable housing. We say to our clients, “if you work the program, the program will work for you.” So we do use that model of self-help and we don’t try to force them but empower them. I’ve heard clients say they know their case manager cares about them, because even after they’ve moved on their case manager still calls them to see how they are. Domestic violence is now more present in the public consciousness than in years past. Do you think the conversation has changed and if so how? Even though we know more about domestic violence, what areas do you think need to be worked on to end it? A year ago, MSP decided to focus on a public health approach to domestic violence. This is a new, and I think, exciting approach. Traditionally, domestic violence was seen as a private family matter, then it was looked at as a law and enforcement issue and a victim services mindset. When the CDC national study came out, the first of its kind, folks started seeing things from a prevention and public health standpoint. At the end of the day if you have 1 out of 4 women and a high proportion of men who are going to become victims, that becomes a challenging situation for the nation to deal with the needs of those victims and prosecute all those crimes. As you would with any epidemic, you have to address preventing the spread of an occurrence if you are going to have any chance of combating the health issue. We started taking that public health lens to begin to see our work from a public health standpoint. You start to look at the community and societal level. You have an extensive resume working in non-profits. What advice would you give about running a non-profit and an organization like MSP. How do you focus on the mission while keeping up with the day to day responsibilities? I think it’s close to 20 years now. Throughout my career, I’ve reminded myself, “it’s about them, not about me.” I had the pleasure of working with a woman who has been working with vulnerable and homeless individuals for 40 years, and she said the same thing. So that’s really helped a lot in terms of my focus. Thinking about it in that way makes things really fall into place. In terms of advice, I probably don’t do a good job of keeping up with the day to day with everything else. Non-profits are probably the most challenging. The range of constituents that you answer to are so astounding. It is beyond what most other organizations have to answer to. You are beholding to your clients, the community, donors, and the local government. Those external relationships make it a really challenging thing to do. I have a lot of experience with crisis management in non-profits. I have a luxury of getting to see many local community based non-profits and that’s given me perspectives you don’t get from one or two places. Others only know the places they have been. That has been something I really value. I guess one of the things that helped me survive is I compartmentalize well. It makes it easier not to burnout because that’s one of the biggest risks in the field. The other thing I tell people is that it is a very small world. You’d be surprised how small it is. Try to be aware and mindful. What are the key warning signs of domestic violence and how can the average person intervene? We think the answer is bystander intervention. Good bystander intervention programs are trying to give people the skill to intervene in helpful ways as well as create this social norm that you should intervene. The sexual assault awareness movement did this. It was seen as a social manner for people not to get involved. We’re trying to make people realize if they see something they should say something, but in a way that’s appropriate to the situation and keeps themselves and the victim safe. This is community empowerment as well. The other thing is trying to help the field develop more sophistication—not all victims are the same and they don’t have the same needs, and not all perpetrators are the same or have the same impact. There are gaps in services for victims besides housing options. For example, middle class women have a gap in services because many middle-class women would be at risk of losing housing, healthcare, and necessities if they left their situations. They would be reluctant to go to a shelter so they tend to stay in situations for even longer. Can you talk about the Clothesline Project and any other efforts MSP is currently a part of? I recently went back through our annual reports. We became the home of the project in the 90s. We have survivors and others impacted by domestic violence make t-shirts about their story. They run the gambit of abuse and trauma to forgiveness and hope to reconciliation and recovery. We display them on clotheslines in the public. One year we were in Freedom Square sewing them, it was a beautiful day. It was an amazing sight, all of these shirts blowing in the wind. We considered it a live art installation. This past year in McPherson square, there’s circular trail and our staffers decided to use that railing to display the t-shirts. We had quite a crowd of people. To me, they’re so inspiring because you see the tragedy but also see how people have come through with this hope. The power and authenticity of stories of domestic violence survivors are unmatched by anyone working in the field. They are their own witness to what they’ve gone through. We are close to 400 volunteers, but I would love to have a volunteer for every t-shirt this October for domestic violence month. Maybe as a potential live art exhibit. Last year we had music and giveaways, and we’re excited about this year’s event. Is there anything else you would like to mention? The main thing we would like to see people do besides the Clothesline Project is follow us on Facebook or Twitter. It’s a great way for people to keep up with us and the community. Interview by Jessica Flores |

Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed